Snares and Pitfalls was the third book to appear under the name of Richard Minne (after the verse book Open House, 1926/1927 and the prose work Heineke Vos and his Biographer, 1933). However, he did not design the book himself: it was compiled by his best friend Raymond Herreman, and Maurice Roelants. If it had been left to the writer himself, hardly any of his work would have been published during his life.

Snares and Pitfalls consists of a strong foreword by Roelants, extracts from letters, verses (including from Open House) and three stories. The quotation at the beginning of this text comes from the introduction (Imprimatur in the Dark), in which Minne thanks the compilers – in whom he has shown blind faith – for the anthology. The thematically arranged letter extracts created the biggest stir. The publication of writings not originally intended for public consumption was new to Flemish literature. Here was a “guy” speaking, a tormented writer who, living a lonely existence in the countryside among his beets and his goats, wrestled with writing his poetry. The title, found on notices on private estates “to warn poachers and vagabonds of hidden snares and self-firing decoys” (Karel Jonckheere), refers to the obstacles between Minne and writing itself; between the writer and the publication – to the wrestling, in other words. According to Minne it meant: “Beware, do not enter the grounds or something unpleasant may happen to you!”

Minne’s poems are unique: the language is clear, simple, traditional. He often uses Flemish words and expressions but they seem comprehensible and never provincial. It is rare to find something so natural that is written in such a formally coherent style:

De Leie en lijkt ons maar een landelijk rivierken,

een wandelende streep, en wat traag water toe,

met aan iederen draai een waaiend populierken,

een half-verdronken ponte, een schilder en een koe.

(The Lys seemed to us just a rural stream,

a wandering stripe, and rather slow too,

with a blowing poplar at every bend,

a half-drowned ferry, a painter and a cow.)

His letters were also completely open and personal. Karel Jonckheere wrote of them: “The successive letters read like a novel. A novel of loneliness, torment, despair and ironic resignation. (…) A letter from Minne is a pleasure. The post office should not charge him for a stamp.’

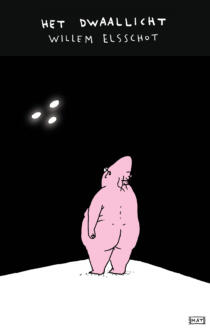

During his life, Minne was appreciated by a modest group of readers in the north and south and by peers such as Elsschot. Later also by Boon, even though he objected, in 1946, to the awarding of the Triennial State Prize for Prose to Snares and Pitfalls due to the lack of “prose”. Boon called him a “tortured sceptic”. But what continues to appeal is the inimitable mix of irony, melancholy and spirit. Jeroen Brouwers once called Minne “that rustic farmer from Elsschot” and the “Flemish cousin of Nescio”, but grimmer, more unpolished, more Flemish and particularly Ghentish. The writer rose in the morning with love as his bedfellow and went to bed with hate.

Minne started out as a rebel and activist and became a poet-farmer. But this also disappointed him and he ended up as a journalist. And all his life he had simply wanted “a nice job, between the Lys and the Scheldt”.

This disillusioned idealist never belonged to any club or coterie of writers. He wrote outside of literary mainstreams, believed in the literature of the greats (Gogol, Chekhov) but not his own, dreamed of a Flemish “Stendhal club” (which never transpired) and admired Paul Léautaud and Cyriel Buysse.

He remained obstinate, contrary and blunt, often scathing. He found Flanders small and petty-minded. Minne airs his gloomy views about the state of Flemish poetry and culture in the final story in Snares and Pitfalls (The Eulogy). Sippe Danneels, a painter, follows the funeral procession of his friend, the poet. The undertakers and a few family members are sidling away from the open grave. No one speaks a eulogy. Until: “ – Guust…Guust my friend… stammered Sippe Danneels… Guust, it is…it is…ha, oh my God!... It’s raining.”