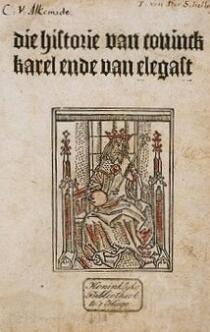

Unfortunately, that work has not survived, but we do know something about it: it was the story of a dream. Kept awake by a dream? How ironic… And so the poet marks the territory within which the story must be understood. He constantly wrong-foots us: his poems are wonderfully ambiguous.

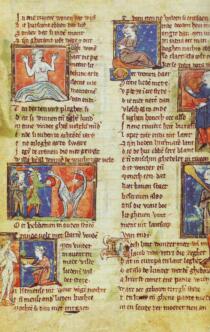

During a day at court around Pentecost, Reynaert the fox is charged for his crimes. The first plaintiff is the wolf Isengrijn. The fox has “verhoert “ (“whored”) the wolf’s wife Haersint (v. 73), by which he means “made into a whore, raped”. But Willem’s target audience has prior knowledge of fox traits and is aware that it could also mean “verhoord” (“heard”) (“fancied”). The she-wolf is indeed not averse to a bit of fun on the side, and her name is not Haersint by chance: a common Middle Dutch term meaning, “it pleases her, she likes it”…

Grimbert the badger will, therefore, have no problem exonerating the fox of rape: Reynaert conducted, so to speak, a courtly love affair and the wolf is only accusing him because he is actually angry with his wife for deceiving him and then “sciere ghenesen” (getting over it so quickly). The poet throws us a wink over the heads of his characters: ghenesen often has an erotic connotation in medieval texts, something like “orgasm”. Willem is playing a clever game with allusions, conventions and expectations. At this point, we are only three hundred verses in, with over three thousand to go…

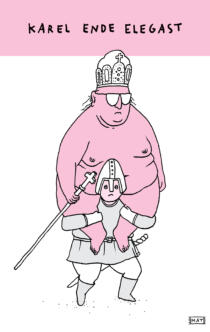

Of Reynaert the Fox is masterfully suggestive. The animals represent - and hold up a mirror to - human behaviour. In this respect, the poem does not provide an edifying view of society. Although the protagonist is extremely intelligent, he only uses his wiles and tricks for his own benefit. The fox is a villain: he murders the daughters of the cock Cantecleer, kills Cuwaert the hare and takes the lives of the king’s envoys (Bruun the bear and Tibeert the tomcat). Furthermore, he accuses his own father of treason and suicide. Reynaert is certainly not a hero. In a 2007 survey by Radio 1, he landed on the list of the greatest villains in literature, described as “cunning incarnate”.

But Reynaert does expose the vices of those around him too. And they are not inconsiderable. The animals/people are incapable of living together in a civilised manner. The values that they hold so dear are hypocrisy, mendacity, voracity, greed and lust. Either one cheats someone or one is deceived. There simply is no middle way. Everyone is looking out for his or her own interests.

Willem the poet did not believe in the utopia that was described in the courtly romances about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, so popular back then, and their noble spirit of self-sacrifice. Instead, he sketched an acerbic, satirical picture of the society and people of his time… and ours.