Robbeknol spends his days looking for food for himself and his master, while the latter prefers to be entertained by ladies of questionable repute. And when Jerolimo’s Amsterdam creditors come to claim their money, Jerolimo vanishes and Robbeknol is back on the streets.

The plot of Bredero’s comic play is actually very simple and the material is not even very original: Bredero took the idea from the Spanish picaresque novel Lazarillo de Tormes (1554). He moved the action from Spain to Amsterdam, which allowed him to add a lot of colourful characters (such as Stingy Geraart and the “sluts” Proper Jans and Pale An) and farcical misunderstandings and to cast a mercilessly critical eye on contemporary society. The result is one of the funniest dramas to emerge from the Dutch Golden Age (and perhaps from all of Dutch literature).

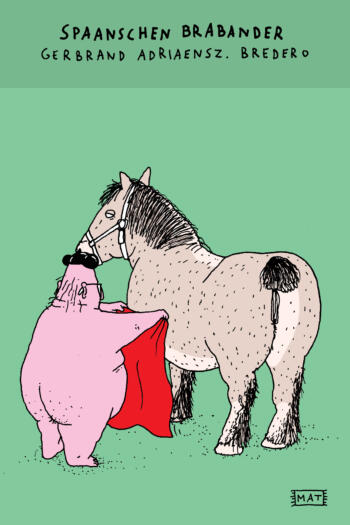

Spanish Brabander can perhaps best be compared to the portraits of Frans Hals: dynamic, lively, characterful faces created with – apparently – spontaneous, even crude, brushstrokes, but always astute and daring.

Spanish Brabander was performed for the first time in 1617 in Amsterdam, but the story is set in the period around 1567-1577. Antwerp was still a prosperous and powerful city back then but in 1617, it was very different. This was a warning from an author who had chosen “things change” as his motto: the tragic citizen of Antwerp of today is perhaps the tragic Amsterdam citizen of tomorrow. In this sense, the play is a reflection of its time, a period in which the rise of the Northern Netherlands ran parallel to the fall of the Southern Netherlands, resulting in a huge wave of immigration to Amsterdam. The haughty Brabanders brought wealth to their new home, but also challenges.

Spanish Brabander is, of course, far more than a period piece. Bredero examined and dissected his characters mercilessly and no one was safe from his razor-sharp pen. Who is in the end the most foolish character in the play? The proud but tragicomic Brabander who has built a sham world, deceives others and is eventually unmasked in an Amsterdam court? Or the Amsterdam people who are so easily fooled by appearances and are left with nothing but unpaid bills? Bredero’s targets are boastfulness, greed, fraud, stupidity, immorality and naivety.

The playful language in the play also sets it apart. Bredero is not afraid to use folk sayings or dialects: every character in Spanish Brabander is given their own characteristic register and dialect. If one wants the full effect, the text should be read out loud and the dialects attempted.

At the same time, Bredero turned against the old-guard rhetoricians and their careless handling of Dutch. He protested the “defilement” of Dutch by the Brabant immigrants. Spanish Brabander is also, therefore, a passionate plea for the Dutch language, and Bredero shows off what that language can do.

Want to find out more?

Spanish Brabanter has often been reprinted since its publication in 1617. Fourteen editions appeared in the seventeenth century and there followed three more (often rewritten) in the eighteenth century. An excellent, more recent edition is annotated and introduced by E.K. Grootes and was published by Athenaeum - Polak & Van Gennep under the title Moortje & Spanish Brabanter (1999). There is a slightly older but perfectly adequate version available from the digital library of the Netherlands (DBNL), edited by C.F.P. Stutterheim (1974).

Theatre companies (both professional and amateur) still occasionally stage Spanish Brabanter. In 1994, there was even a musical version made of the play.