The collection Poems, Songs and Prayers, 1862, is important from a literary-historical perspective due to its innovative nature but it was, in fact, a collection of religious poetry intended for a limited circle of pupils. Wreath of Time (1893) was a mixed assortment of personal poetry that included many occasional poems. A poor reception unites the two, with neither the public nor the critics appreciating the quality of the works.

With Garland of Rhymes, Gezelle hoped to be recognised and understood as a poet. This was to be in vain. Only a couple of the influential critics of the day (such as Albert Verwey) praised the book. Gezelle did receive the Five Yearly Prize for Dutch Literature, but it was awarded posthumously.

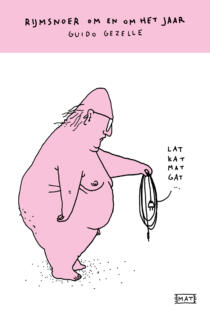

In Garland of Rhymes, the much older poet collected the harvest of his final years (1895-1897), during which he had been phenomenally productive. He supplemented these poems with reworkings of earlier pieces. What makes this volume exceptional is the arrangement of 231 poems and short verses (without counting the introduction and appendix) in one monumental cycle, organised according to the months of the year. The poems thus follow a continuous timeline within a closed order. The full title, Garland of Rhymes Around the Year, makes reference to this. Gezelle himself called the title a poetic diadem, a binding that is wrapped around and around the years.

The personal experience of nature as the seasons change fits within a larger context. The shifting moods of the lyrical self are given their place in the image of an orderly cosmos in which the hand of God is always visible and tangible, or better, made tangible by the poet. Hence the remarkable realism in the collection, the attention to the smallest details in nature and the use of an impressionistic style to express sensory experiences – seeing, hearing, tasting and smelling.

As is the case with the great impressionist painters (especially Van Gogh), the attention is shifted from what has been observed to how: the process and the material form that is given to this observation. In the case of the poet, the language and the form of the poem constitute this matter. In Garland of Rhymes, we see a poet who, between hope and despair, repeatedly takes on the difficult task of using language to elicit the deepest secrets of things and to express a divinely animated world.

Language and form are thus central to this collection. We can see this in the original idiom (enriched by the old Flemish lexicon) and a colourful variety of poetry in terms of rhyme, metre and strophe construction. Gezelle was so focused on the form that he even paid attention to the typography. He broke the conventional rules with his unusual and virtuoso indents and outdents that reinforced the rhythm or the meaning of the verses and proved himself to be a true contemporary of poets like Mallarmé. He also anticipates modern visual poets of the twentieth century, such as Apollinaire and Van Ostaijen.

In Garland of Rhymes, we have the pleasure of witnessing Guido Gezelle - the grand master of Dutch literature - at the height of his powers.