So began the Flemish writer Marnix Gijsen’s hymn of praise for a novel that would soon become an iconic book of Flemish literature.

The novel follows the fortunes of its protagonist in the former colony during the period 1955-1960. The first-person form used by the narrator and the urgency of his voice creates the impression of autobiographical authenticity. The focus is very much on his countless sexual adventures with black women, on his urge to immerse himself in the primitive, paradisiacal nature and on his abhorrence of white, Western, Christian culture.

In this sense, the book is a classic example of cathartic writing: each step deeper into this mythical Africa is experienced by the narrator as both an initiation and as a liberation from the straitjacket of what he calls the “frustro-purito-christo-racist syndrome”.

Gijsen characterised Geeraerts’ style as “flowing like lava”. Geeraerts barely gives his readers time to breathe, dragging them along in an almost uninterrupted stream of words and making them complicit in his obsession with vitalism.

Naturally, not everyone was as enthusiastic as Marnix Gijsen. Both the subject and the appearance of autobiographical realism in Gangrene created considerable controversy and even uproar. Some critics, especially Catholics, were disgusted by the shameless sexuality on display while others accused Geeraerts of racism and colonial despotism.

The clash between literary and ethical opinion reached a remarkable climax in 1969. A few weeks after the novel was awarded the triennial State Prize for narrative prose, the then Minister of Justice, a socialist, ordered the seizure of the book on the pretext that it was morally degenerate and racist. The removal of the book for several days as well as the somewhat comical furore made the book a commercial success. While it had taken two years for a second edition to be printed, after two more years Gangrene was on its twelfth printing.

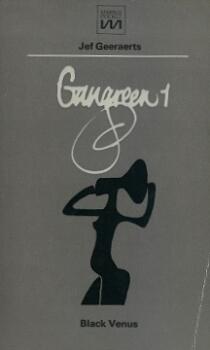

Whatever people might think half a century later about the ethical aspects of the novel, there can be no doubt that with Gangrene, Jef Geeraerts was one of the first to raise “Flemish Congo literature” to the level of literature. He had already made a start with his debut I’m Just a Negro (1962), followed by Matsombo’s Story (1966), but the bravado with which he juxtaposes the extremes of erotic and cosmic ecstasy in the explosion of vitality that is Gangrene with moments of tenderness, sudden violence and a bitter cultural critique, makes this novel unlike any other of its time.

Translations:

Geeraerts, Jef. Im Zeichen des Hengstes German / transl. from Dutch by Carl Peter Baudisch. München Nymphenburger, 1971. Fiction, gebonden. Original title: Gangreen I Black Venus. Brussel Manteau, 1967. Present at the library of the Nederlands Letterenfonds.

Geeraerts, Jef. Im Zeichen des Hengstes German / transl. from Dutch by Carl Peter Baudisch. München Heyne, 1984. Fiction, Original title: Gangreen I Black Venus. Brussel Manteau, 1967. 11e dr., 1e dr. deze vertaling: 1971.

Geeraerts, Jef. Im Zeichen des Hengstes German / transl. from Dutch by Carl Peter Baudisch. München Heyne, 1973 (Heyne Buch; 5008). Fiction, paperback. Original title: Gangreen I Black Venus. Brussel Manteau, 1967. Present at the library of the Nederlands Letterenfonds.