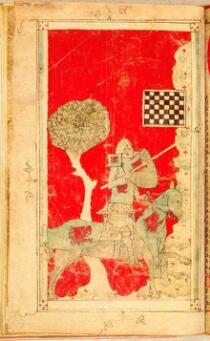

When the chessboard vanishes through one of the windows, Arthur calls on his knights to go and bring him the board, three times. In vain. Only when the king solemnly swears that whoever brings him the board will inherit his kingdom does Walewein, the finest of Arthur’s knights, take on the challenge.

This opening scene sets the tone but that tone will continually change throughout the 11,000 verses: from heroic to ironic, from exemplary to questionable, and back. Walewein is certainly an excellent knight: he slays dragons and robber barons, defends damsels in distress, gives defeated opponents a second chance, lends his faithful horse Gringolet to a young boy who has been robbed of his own, gives the last rites and a Christian burial to an angry knight, etc. And he always washes his hands repeatedly after he has eaten.

But at the same time, he lets a fox steal his weapons and horse, does not dare to cross the sword bridge – unlike Lancelot in other romances –, falls asleep, resulting in his sweetheart being kidnapped, is very slow to tell her that he took her from her father’s realm on someone else’s instructions, and he does not seem to mind that she returns home to her father like a good girl at the end of the story.

A mixture of chivalrous courtly idealism and burlesque situations make this work difficult to fathom and all the more interesting because of it. When Walewein storms the fortified castle of King Assentine, he single-handedly defeats so many opponents that they think there is an entire army at their gates. In utter confusion – in the style of modern-day comic strips – they end up attacking each other in the dark. Ysabele, who is head over heels in love, is able to obtain access to the dungeon on the pretext that she will torture the prisoner Walewein, but in actual fact is intent on tasting love to the fullest. But however sweet she may seem, it seems that she cannot think of a better way to keep a tunnel secret than by drowning the architect, in the same way that she does not bat an eye as she urges Walewein to cut off the head of a knight who is lying defencelessly on the ground.

Penninc and Vostaert have delivered a work that both follows the conventions of Arthurian romances and turns them on their head. They creatively deployed a wide arsenal of themes and motifs that originate from all sorts of genres. The outline of the romance and the motif of the enchanted fox that acts as a helper, must both have originated from oral tradition. Whether or not this is the case, there is a close link with the fairy-tale of the golden bird that the Brothers Grimm recorded at a much later date: a young hero can only apprehend the golden bird if he can exchange it for a valuable horse that in its turn must be traded for a beautiful princess.

Walewein can only obtain the chessboard in exchange for the sword with the two rings and that sword only in exchange for the peerless Ysabele. But the authors also made use of motifs from French and Dutch Arthurian literature, the Tristan theme, the bible, the letter from the legendary priest-king John, the visionary literature harking back to Irish tales, beast fables and so on.

Using all these ingredients, they composed a rollercoaster of a tale that playfully illuminates the paradoxes of life and keeps the readers in suspense right until the end.