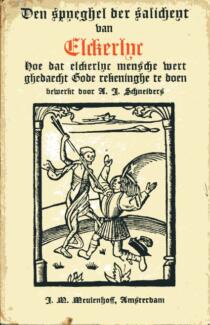

The anonymous author of the play, who remains unknown to this day, portrayed the sudden confrontation of humans with death in a very direct and literal manner. To this end, he used characters that are not individuals but personifications of abstract concepts. Elckerlijc, which literally means “every man”, is told by Death that he must embark on a pilgrimage from which he will never return. He has to answer to God for his sinful and all too materialistic way of life.

Elckerlijc is granted one concession from Death: he can bring a travelling companion with him. That is, if he can find someone who is willing. Elckerlijcs friend (Companion), family (Relative and Cousin) and material possessions (Goods) soon abandon him. His wisdom (Wisdom), strength (Strength), beauty (Beauty) and five senses (Five Senses) initially seem to support him but they too demur once the grave is in sight. Self-knowledge (Knowledge) points out the importance of virtue (Virtue) but Virtue is too weak at first to help the protagonist. Only after Elckerlijc has confessed and done penance does Virtue return to accompany him on his last journey.

There is possibly no other piece of Dutch-language literature that has had such a broad and lasting influence on world literature as Elckerlijc. The work achieved success soon after what appears to be an early translation and adaptation into English (Everyman), Latin (Homulus and Hecastus) and German (Hekastus). The English translation led to a revival of interest at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Irish poet W.B. Yeats adapted it, as did the German playwright Hugo von Hofmannsthal (a version that to this day opens the famous annual Salzburger Festspiele). In 2006, the American author Philip Roth published his Everyman, in which the action is moved to twentieth-century North America.

The particular appeal of Elckerlijc lies in the distilled, almost abstract treatment of a universally recognised theme. Everyone will be confronted one day with his or her own mortality and with the question of what they have done with their life. This question was raised in countless other texts and artworks in the late Middle Ages – an era that was obsessed with the ars moriendi (art of dying).

But what makes Elckerlijc so exceptional is its simplicity. The action takes place over one day. Elckerlijc is in every scene: there is no subplot of any kind. And the language is so clear and to the point that even the modern reader can understand the text with a minimum of definition checking. It is one of the few late-medieval plays in which the allegorical characters do not alienate modern readers but rather appeal to them through their timeless familiarity.